How A Secular Democracy and Religious Pluralism Paved the Way for Women's Rights

A lookback on American feminist history

America has never been a monolith, despite the aspirations of its earliest settlers to form these lands into their idea of a spiritual haven. As immigrants from all over the world came to America - either fleeing their home country, enslaved by the ruling class, or in hopes of building a world tailored to their views - America reckoned with the diversity of cultural and religious pluralism. While some folks had of mind to install a Christian, patriarchal, white supremacy government, others pushed for a separation of church and state, a concept unheard of before the founding of the United States. The separation of church and state forced American society to handle morality and legislation amongst its citizens without the dominance of one religious view granted by the State.

This secularization of government disrupted what it meant to be a citizen and who could hold power and privileges. No longer bound by a singular religious doctrine or perspective, the people had the power to control what their society looked like. The variety of approaches to citizenship and rights fostered the path for non-Christian (or conservative Christian), non-male, and non-White voices to emerge. This essay focuses on the role women played in advancing rights not only for women but for others marginalized by the dominance of the conservative Christian patriarchy in power. It will examine the role of religious pluralism in unfolding women’s rights from the colonialism of the seventeenth century through the twenty-first century. It will consider how women played a central role in developing the education, healthcare, non-profit, and private sectors, and the arguments for and against women’s suffrage and civic advancement.

The first influential woman of religion and American history was not an American and never set foot on American soil. Queen Isabella of Spain, with her husband, King Ferdinand II, financed Christopher Columbus’s expedition to the Americas on behalf of the Spanish Crown and Catholic Church in 1492. Columbus’s recounts of his violent rampage through the Americas would serve as a message of inspiration to countless Christian Europeans who traveled the seas to claim their territory in American and establish a life different than their experience in native Europe.

Ship by ship, hopeful religious Europeans set foot in the “New World,” prayerfully imagining this New World that was ordained by God in light of the Protestant Reformation, religious persecution, government oppression, and horrid farming and living conditions they left behind. They were people of faith, and in the face of diversity of languages, cultures, and theologies, they each felt a claim to their God and their faith’s mission in the “New World,” but “as to their Religion they are very much divided.” Many of those settlers arrived with funding from their religious denominations back home. They quickly got to work establishing laws and legislation on the rights and privileges amongst the rising competition of religious pluralism and against the perceived enemy, Native American populations, whom they enslaved and killed to the dismay of the Pope. Catholics and Protestants were not alone. Jews, Quakers, and Africans arrived either willingly or as slaves, further diversifying religion and culture with their customs and beliefs.

The religious diversity and fracturing were not just amongst religions but within denominations, such as the Puritans. Anne Hutchinson, an outspoken Puritan Christian woman in Boston, was inspired by reforming minister John Cotton and garnered support from her followers. Her actions were a form of feminist theology, and her existence was validated by God, not by patriarchal social order. Within two years of her 1634 arrival in America, she was denigrated, banished, and killed for her public opposition to ‘religious rules rather than God’s free grace and salvation.’ She was not alone in dying at the hands of the Christian conservative patriarchy – the killing of women thought to be ‘witches,’ an especially violent crusade that persisted predominantly in Great Britain, Germany, and France and was further implemented by fundamentalist, sexist Puritans at the Salem Witch Trials until 1693.

It was not only to white audiences that Christian women sermonized. Sarah Osborn ministered to African slaves in Rhode Island in the 1760s. She held services to Africans and whites, garnering as many as 500 people in attendance at her lectures. This struck at the heart of American racism, white supremacy, and exploitation of labor for the benefit of the ruling class.

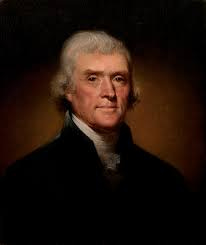

The American Revolution, a Protestant-born movement against British tyranny, allowed American political leaders to consider the failures of past religious and government institutions and write governing documents for the new nation. The Constitution of 1787, amended in 1791, called those first ten amendments the ‘Bill of Rights’. The First Amendment prohibited the establishment of religion by the State and protected the freedom of worshi,p and was further cemented by Thomas Jefferson’s (a deist who owned a Quran!) bill ‘Establish Religious Freedom’ to all religions. Though this did not include Native American religions, this did prevent any one religion or denomination from exerting federal powers and acknowledged the diversity of ethnicities and beliefs that comprised the American people. This was not to say American society agreed with the Founding Fathers' religious tolerance. This period of religious revivalism following the American Revolution is known as the Second Great Awakening. While the First Great Awakening of the 1700s battled over which religion/denomination would become the central governing/social institution, the Second Great Awakening saw a separation from institutions and a call to return to God for the nation to be carried out in the 1800s.

Though power and freedom were confined to the men, there were seeds of empowerment planted in the 1700s. Colonial Baptists and Quakers were two such groups where women began finding their footing. They could not be ordained, but they did make up the vast majority of participation in the congregations, and they were empowered by their interpretation of Scripture to be actively engaged in their local communities and to vote within denominational elections. The American Revolution would overturn much of this progress for equality and leadership amongst the women in Puritan, Quaker, and Baptist traditions, once the oppressed tasted freedom, that taste would be hard forgotten, as we shall learn in the 1800s section.

In the Second Great Awakening, the churches sought separation from the government and taxation and looked to move forward with their theological agendas. They affirmed they could do this best unencumbered by the State and motivated by a millennialism belief that society's actions were paving the way for a Second Coming of Christ. The ideology centered on the ‘Benevolent Empire’ that white Christians served God’s will through benevolently colonizing, educating, and Americanizing non-whites and non-Christians through imperialism.

The reordering and restructuring of individual denominations also indicate a changing society. One such example was the patriotic allegiance within the Anglican Church settlements in America, which forced a separation into a new identity called the Protestant Episcopal Church. The citizens no longer felt connected to the English Crown and instead formed their identity as Americans with the purpose of evangelizing and nation-building. The Methodists also shared this sentiment, founded by Anglophile John Wesley. The Methodists split from their Anglican allegiances and established the Methodist Episcopal Church. Furthermore, denominational schisms led to increased splits, which reduced individual denominational power. The Stone-Campbell movement, leading to the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), sought to unify Christianity in the face of this division.

Women and religion evolved in tandem in Antebellum America. Through religion, many women gained influence and power. Dorothy Ripley was empowered through her evangelical church to preach at the House of Representatives in 1806, in addition to Phoebe Palmer, who advocated for women to speak in church. Catherine Beecher, an established reformer, was able to align with the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) to petition to stop the Native American genocide. Unitarian Hannah Adams compiled her book An Alphabetical Compendium of the Various Sects Which Have Appeared in the World from the Beginning of the Christian Era to the Present Day to recognize and legitimize the variety of faiths in America.

Social issues such as slavery, women’s suffrage, literacy, mental healthcare, and alcoholism became central to Christian rhetoric. Quakers had long opposed alcohol consumption, but they also became vocal opposers of slavery. Angelina Grimke, a Quaker, ruffled feathers when she publicly spoke out against slavery, questioning the men’s singular authority to be the arbiters of social policy and arguing that women could not be free unless slavery was abolished. Her vocal opposition tested the predominantly Episcopal slave-holding male elites of her native South. The aforementioned reformer, Catharine Beecher, opposed Grimke, claiming ‘domestic feminism’ and advocating for women to remain in the home and out of politics. Beecher’s rhetoric concerning the importance of women’s role in the domestic sphere later motivated women to travel with their husbands out West and be at the center of nation-building from the home. Many women were inspired by Beecher’s feminine domesticity argument to move West, raise Christian children and homes, and avoid participation in the political sphere. Slave-born and Methodist-raised Isabella Baumfree, also known as Sojourner Truth, lobbied President Lincoln on behalf of slaves for legislation to protect, educate, and resettle freed slaves and advocated for reform in nutrition, clothing, and hygiene. Harriet Beecher Stowe, a daughter of a Presbyterian minister and sister to Catherine, used her book Uncle Tom’s Cabin to depict the brutality and un-Christian character of the slave system to her Northern readers, stirring sentiment and advancing the abolitionist cause in the 1850s.

Former Presbyterian Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Quaker Lucretia Mott organized women in Seneca Falls under the Women’s Rights Convention of 1884 to ignite the discussion of the rights and freedoms of women in tandem with abolition. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Matilda Joslyn Gage, and Susan B. Anthony would go on to publish the Declaration of Rights of Women, which argued women should have equal rights to men.

Christian women of the nineteenth century also ventured into health and medicine, particularly as academia and modern medicine developed from the Enlightenment Age and in the face of alcoholism. Dorothea Dix, a Unitarian reformer, focused her mission on healing the sick and passing legislation to found or expand thirty-two mental hospitals. She became superintendent of women nurses, the highest officer held by a woman in the Union Army. Mary Baker Eddy, the founder of the Church of Christ Scientist, a denomination that balked at modern medicine and public health information, believed that illness was a manifestation within the soul and that through following the Bible and Jesus, one can heal oneself and others, and looked to Jesus as a Healer. Ellen G. White of the emerging Seventh Day Adventists denomination (founded at the same time as the Mormon Church) believed that the body should be free of alcohol, narcotics, and stimulants, including all forms of caffeine and tobacco, thus clearing the body to properly prepare for Christ’s coming. Meanwhile, Methodist Frances Willard, president of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, advocated for women’s suffrage and the right to work in the commercial and political sectors. She was a crusader for anti-prostitution and child protection laws. Furthermore, the advancements in medicine enabled medical-induced pregnancy termination amongst those who could afford it, which became a controversial topic amongst economic classes and religious folks alike. The right for a woman to control her body would be hard-fought: the Comstock Act of 1873 prohibited the sale and distribution of information and medicine related to birth control. Despite childbirth historically seen as within the woman’s domain, the American Medical Association, comprised of educated and privileged men, was now making decisions for women’s healthcare and fertility and was the primary authority on healthcare laws. Notable women’s healthcare activist and abortion advocate Margaret Sanger was jailed and denigrated for her work towards what she called ‘Voluntary Motherhood.’ Those who held power and resources had access to birth control but restricted access from women and lower-income people, who were considered second-class citizens. Therefore, birth control and women’s healthcare were less about morality and more about who had access to and control of it.

Much of the women’s suffrage movement was fought out in the American West, where many new states’ constitutions had yet to be written, and “the vast region's settlement disrupted society's rules of the game enough to give determined women opportunities to become more equal by acting more as equals.” The West was sparsely populated, and decisions about property, education, and employment needed to be made in light of widows or abused wives and children. Could women own property if the husband died? Could they attend school and receive training to work and gain income to afford the property? They would have to — the small tax base couldn’t afford to make women wards of the state, nor could they spare the labor and necessary training for that labor for their communities to grow. Could they divorce their alcoholic husband and keep custody of their children out of safety from said alcoholic husband? All of these questions were answered if women had the right to vote, for if managing property and businesses meant they would owe taxes, America was founded partly on the argument of taxation without representation. Furthermore, divorced women needed divorce lawyers, and who better to trust to represent them than Clara Foltz, a divorcee´ turned divorce lawyer and one of the first lawyers on the West Coast. Furthermore, the influx of Jewish immigrants brought the Jewish perspective of marriage to the conversation. Henrietta Szold, a Jewish speaker at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, argued that the Jewish approach to marriage and divorce was one of a social contract with underlying sacred spirituality, as opposed to Catholic and Protestant views that marriage was a sacred bond with an underlying social contract. The mix of religious perspectives on marriage would disrupt the sanctity of marriage, particularly as the hierarchy of the home was a form of control for the patriarchy.

With women involved in the home, church, and business, it was the next natural step to enable women to vote; Western woman’s rights activist Clarina Howard Nichols stated in her address at the Second National Woman's Rights Convention: "It is only since I have met the varied responsibilities of life, that I have comprehended woman's sphere," she wrote, "and I have come to regard it as lying within the whole circumference of humanity.” Harriet Hattie Redmond, president of the Colored Women’s Equal Suffrage and based out of Oregon, supported Nichols. While very few of the Western women’s arguments for equality were inspired by religion, the patriarchal Christians of the West, especially the Mormon men, and back East and down South fought against such ideas, and the sparse pioneer country allowed the society to be much more open and tolerant to women’s advancements. However, the population scarcity and the frontier settlers’ disgust with oppressive legalism allowed greater experimentation with democratic ideals.

The 1900s would see the fruits of the women's labor who fought for centuries leading up to it. White women gained the right to vote in 1919, and the right of suffrage for all people to vote was won in the Voting Rights Act in 1965, almost two hundred years after our country's founding. Native Americans, sadly, were not protected to publicly worship, use sacred objects, or access sacred sites until 1978’s Native American Religious Freedom Act. While women like Amina Wadud, a black Muslim, have continued to fight for the acceptance of Muslim culture and her feminist interpretation of the Quran to empower Muslim women in the workplace, the successes of our ancestral mothers remain unsecured. At every step of women and religious advancement, the patriarchal Christians of the Right in power have been right there to challenge equality and prevent the loss of power. Sanger’s fight for women’s right to bodily autonomy was not achieved until the court ruling of Roe vs. Wade in 1973, which was overturned in 2022. Racism and sexism are nowhere near concepts of the past but remain clear and present through the rhetoric espoused by the Right’s leaders. At every turn, the rhetoric against women’s liberation is met with accusations of heresy and hysteria.

Though American women live in 2024 with many more rights and freedoms than the women had before them, the Red Wave of the recent election jeopardizes those freedoms, with major organizations like the Heritage Foundation and Turning Point USA releasing Project 2025. If implemented, Project 2025 will roll back the advancement of women’s rights around bodily autonomy and divorce. The narrative regarding diversity is just as fear-mongering as it has been since our earliest colonial days; the desire to make America into a haven for Christian whites is still just as present.

When Americans hear the phrase ‘one nation under God,’ they must first ask, ‘Whose God?’ Our Founding Fathers legislated a democratic, secular nation at its founding, and despite the near-deification of these men, their words have been challenged by the Religious Right, which seeks to maintain a government that prioritizes a Christian patriarchal white supremacist power. Democracy is bolstered by religious pluralism, and the freedoms of women and the marginalized are protected by democracy. Should we fall into religious tyranny, we will no longer be the Great American Experiment of democracy, and our government will look similar to the England we revolted against.

Bibliography:

Avalon Project. Privileges and Prerogatives Granted by Their Catholic Majesties to Christopher

Columbus: 1492. Yale Law School - Lillian Goldman Law Library, Accessed 14 Nov. https://avalon.law.yale.edu/15th_century/colum.asp.

Barnett, Lisa. “Week 1 Lecture”. Canvas lecture, Phillips Theological Seminary, Tulsa, OK, August 27, 2024.

Barnett, Lisa. “Week 3 Lecture”. Canvas lecture, Phillips Theological Seminary, Tulsa, OK, September 10, 2024.

Barnett, Lisa. “Week 4 Lecture”. Canvas lecture, Phillips Theological Seminary, Tulsa, OK, September 17, 2024.

Beecher, Catherine. An Address on Female Suffrage. Teaching American History. Accessed November 14, 2024. https://teachingamericanhistory.org/document/an-address-on-female-suffrage/.

Beecher, Catherine. Addressed to Benevolent Ladies of the United States. Teaching American History, https://teachingamericanhistory.org/document/circular-addressed-to-benevolent-ladies-of-the-united-states/, 1829.

Butler, Jon, Grant Wacker, and Randall Balmer. Religion in American Life: A Short History,Second Edition. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Comstock, Anthony. Chastity Laws. PBS: American Experience. Accessed May 23, 2024. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/pill-anthony-comstocks-chastity-laws/.

Congress. American Indian Religious Freedoms Act. Congress. Accessed November 14, 2024. https://www.congress.gov/103/bills/hr4230/BILLS-103hr4230enr.pdf

Dyer, Mary. “Letter from Mary Dyer to the General Court and Testimony”. Teaching American History. Accessed November 14, 2024. https://teachingamericanhistory.org/document/letter-to-the-general-court-and-testimony/

Eddy, Mary Baker. “The People’s God: Its Effect on Health and Christianity”. Teaching American History. Accessed November 14, 2024. https://teachingamericanhistory.org/document/the-peoples-god-its-effect-on-health-and-christianity/

Ellen, Charlotte. “Sexism.” In The Concise Dictionary of Pastoral Care and Counseling, edited by Glenn H Asquith, 131. Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press, 2010.

Gallagher, Winifred. New Women in the Old West: From Settlers to Suffragists, an Untold American Story. New York: Penguin Press, 2021.

Griffith, R. Marie. American Religions: Hannah Adams. American Religions: A Documented History. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Grimké, Angelina. “Appeal to Christian Women of the South”. The American Yawp Reader. Accessed November 14, 2024. https://www.americanyawp.com/reader/religion-and-reform/angelina-grimke-appeal-to-christian-women-of-the-south-1836/.

Miller, John. “As to Their Religion, They Are Very Much Divided”: Pluralism in Colonial NewYork”. Teaching American History. Accessed November 14, 2024. https://teachingamericanhistory.org/document/as-to-their-religion-they-are-very-much-divided-pluralism-in-colonial-new-york/.

Nichols, Clarina Howard. “The Responsibilities of Women”. EdChange - Advocating Equity in Schools and Society. Accessed November 14, 2024. http://www.edchange.org/multicultural/speeches/nichols_responsibilities.html.

Pannell, William. “Racism.” In The Concise Dictionary of Pastoral Care and Counseling, edited by Glenn H Asquith, 124. Nashville: Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press, 2010.

Pope Paul III. “Papal Bull: Sublimus Deus” (1537). Papal Encyclicals. Accessed January 15, 2025, https://www.papalencyclicals.net/paul03/p3subli.htm.

“Project 2025”. Project 2025.org. Accessed November 15, 2024. https://www.project2025.org/

Redekop, Calvin. “Power.” In The Concise Dictionary of Pastoral Care and Counseling, edited by Glenn H Asquith, 118. Nashville: Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press, 2010.

“Roe vs. Wade”. Reproductive Rights.org. Accessed November 15, 2024. https://reproductiverights.org/roe-v-wade/.

Sanger, Margaret.“Voluntary Motherhood”. Teaching American History. Accessed November 14, 2024. https://teachingamericanhistory.org/document/voluntary-motherhood/.

Stanton, Elizabeth Cady, Gage, Matilda Joslyn, and Anthony, Susan B.. “Declaration of Rights of the Women of the United States.” Teaching American History. Accessed November 14, 2024. https://teachingamericanhistory.org/document/declaration-of-rights-of-the-women-of-the-United-states.

Szold, Henrietta. “What Judaism Has Done For Women”. Speaking While Female. Accessed November 14, 2024. https://speakingwhilefemale.co/religion-szold/.

Wadud, Amina. “Citizenship and Faith”. Teaching American History. Accessed November 14, 2024. https://teachingamericanhistory.org/document/citizenship-and-faith/.

White, Ellen G. Stimulants and Narcotics. Teaching American History. Accessed November 14, 2024. https://teachingamericanhistory.org/document/stimulants-and-narcotics/.

Zulkosky, Patricia. “Feminist Theology.” In The Concise Dictionary of Pastoral Care and Counseling, edited by Glenn H Asquith, 97. Nashville: Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press, 2010.